“Um dos aspetos da desigualdade é a singularidade - isto é, não o ser este homem mais, neste ou naquele característico, que outros homens, mas o ser tão somente diferente dele.”

Fernando Pessoa

It is fair to claim that we are witnessing a revival of interest in the search for the determinants of the gender wage gap under new empirical approaches, richer data, and renewed theoretical perspectives. Gender equality is an important sustainable development goal (#5) but it might be further away to be accomplished than we would expect.

According to UN data, women earn on average less than men, to be precise, women earn less 24% than men, globally.

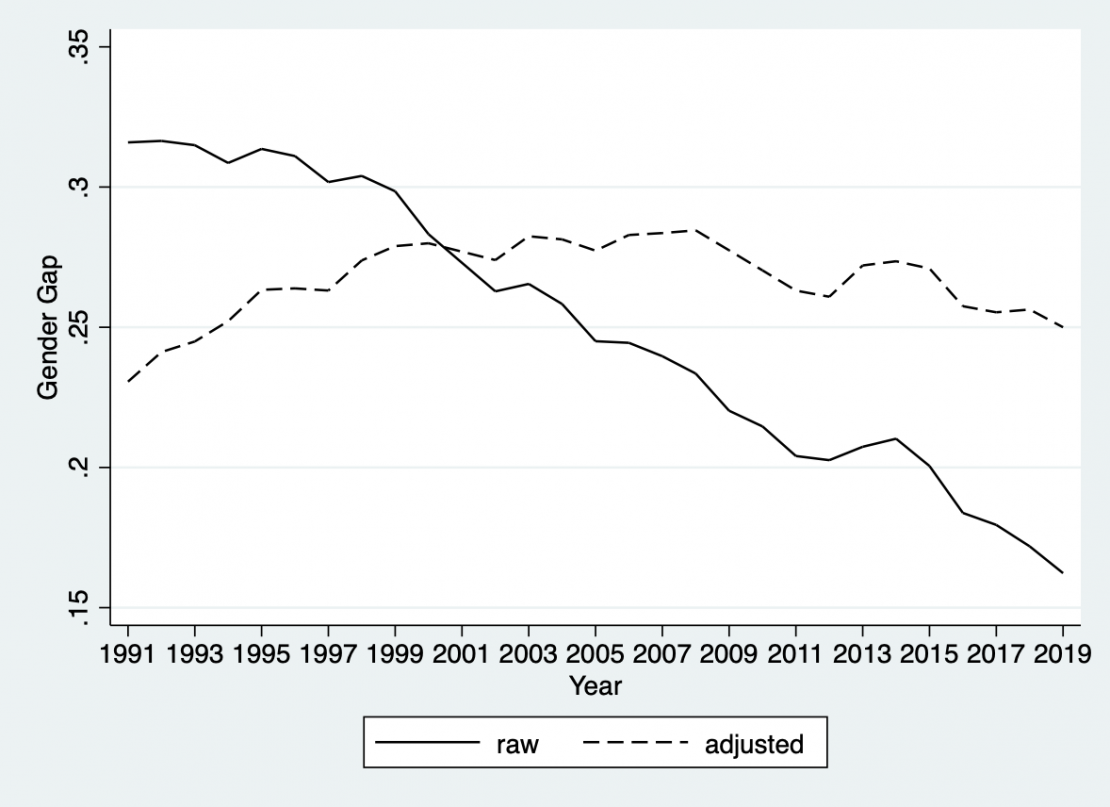

In order to understand how far we are from achieving this goal, we need to look at the trend in the last years. Looking in Portugal at the last 30 years (1991-2019), the raw gender base wage gap was reduced from more than 30% to 16% (raw line, figure). At first glimpse this looks like great news.

Traditional economic analysis had focused primarily on (1) the importance of female labor force participation; and (2) differences in observable attributes between men and women on the gender pay gap. Both of these two mechanisms can be understood intuitively.

If the female participation rate is low, there is scope for the attributes of employed women to be unrepresentative of those of the female population in general. This selection could operate to raise or lower females’ wages relative to males, depending on whether social norms, preferences, economic conditions and public policies disproportionately attract into the labor market more or less qualified women. In any case, as the female participation rate increases, the importance of selection influencing the gender pay gap is expected to decline. Since 1991, in Portugal women dominated the labor market inflows, particularly better skilled women. This evolution translated into a 11 percentage point increase (from 35 to 46 percent) in the feminization rate of the stock of employed workers.

We know that the convergence in attributes such as education and experience played a key role reducing the gender pay gap. By 2019 women working in Portugal already possess observable characteristics that enhance productivity identical to their male counterparts. Women are now better educated, participate more in the labor market and have longer tenure in the firms. The improvement in the wage outcome of the women is fully accounted by the catching up of their skills in comparison to males, after three decades of human capital investments.

However, what do we mean with gender wage equality? We expect that similar individuals earn the same, but comparing men’s average wage with women’s average wage is not enough and potentially misleading. Equality means that individuals, all else equal, earn the same. Thus, we need to compare women with men with similar characteristics. The relevant comparison is between a man and a woman that has the same age, tenure, level of education, occupation and job title working in the same firm. If we take into account these characteristics of the workers to compute an "adjusted" gender wage gap, there is no longer an indication of improvement of gender wage equality (dashed line, figure). In other words, the wage improvement achieved by women over this period is due to the catching up of their skills (education, labor market experience, seniority, etc.) not by a reduction in unexplained component of the wage difference, which is conventionally equated to gender discrimination. Gender discrimination, in this sense, was not reduced, on the contrary, it slightly deteriorated over the 30 years period.

This means that the adjusted gender wage gap remained roughly constant at around 26 percent over this period. An average woman with the same firm size, age, education and experience earns less 26 percent than the counterfactual man. With the detailed data and the available econometric techniques we can go even deeper. If we consider a woman that has the same age, education, experience and works in the same firm in the same job title and occupation, she actually has earned always 12% less during the all period. In the last 30 years nothing change significantly in this regard.

After investigating the sources of the wage gender gap, we conclude that sorting among firms and job-titles can explain about two fifths of the wage gender gap. The allocation of female workers to firms and job-titles did not improve over the last three decades. In fact, it deteriorates somewhat, since in 2013 females tend to be less present in firms and job titles with more generous wage policies.

Plausible explanations highlighted by Blau and Khan (2016) include differences in psychological attributes (for example, competitiveness and bargaining power) that would penalize women at the top of the skill and job ladder, compensating differentials for characteristics of the top jobs (for example, longer and less flexible working hours), and pure discrimination.

Have a great and impactful week!

Pedro Raposo

Assistant Professor of Microeconometrics

CATÓLICA-LISBON

This article refers to edition #147 of the "Have a Great and Impactful Week" Newsletter and covers SDG x.

Subscribe here to receive the weekly newsletter